Global Institutions

Do they have the leadership and capacity to deal with the tasks ahead

Where only a few months into the crisis that now seems certain to result in changes for capitalism, economic development and the role for global institutions in the future. I wanted to explore how these global institutions and their government masters will meet the serious challenges ahead. I also hoped I could follow my theme on leadership as this is going to be more important than ever at these institutions.

The forthcoming G20 in April could prove to be one of the most important meetings since the Second World War – top officials have expressed concern that if it fails to provide the required leadership that the global institutions will lose relevance. The financial crisis has created a moment of truth for these institutions with some estimates that a staggering $US50 Trillion has been wiped off the value of financial assets.

With leadership and global governance today taking on a new level of urgency for all of us who reside on this planet we must question the role and success record of these global institutions as no single government can any longer deal with the complex issues that transcend borders.

Only a year ago, the chairman of the Bank of England was questioning the relevance of the IMF now the British Prime Minister Gordon Brown is proposing to make the IMF and its reform the central issue for the G20 that is to be held in London. Leadership is going to be critical and time is the essence – it is good news that the new US president is attending. Gordon Brown has already been to Washington to meet President Obama to talk about his ‘global grand bargain’ the centerpiece for the G20.

Past efforts at reform have not been successful and even following the Asian crisis ten years ago little progress was made. I had planned to say some rather unkind things about the UN, and other global institutions such as the IMF but most of it has now been said. The IMF is only one of many of these institutions to have a dubious track record when it comes to the successful execution of their role. A deeply rooted culture is evident which will be exceptionally difficult to change. The same ideas that have failed in the past quickly return to the menu.

The global leadership at the time the Bretton Woods organizations were set up in 1944 had the advantage of a single focus – to rebuild following the devastation of WWII. The London meeting will have a very much more complex agenda.

Reforming global institutions is akin to attempting to quickly change the direction of a giant aircraft carrier and as difficult as this is it’s even harder if not almost impossible to change the culture of organizations that have been 55 years in the making. A lot of

The conference that took place at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods that gave birth to the IMF, World Bank

President Roosevelt and other leaders and their advisors were fully aware of the scale of the task to rebuild the majority of the world’s industrial nations. This was true leadership on a scale not seen before or since.

For the current crisis, there isn’t a single country to lead as there was at the end of WWII when the engine of the US economy was operating at full throttle as a result of the war. The recent shift of economic power to Asia is an important factor today, but even China is a relatively small economy, three to four trillion dollars when contrasted to almost fourteen trillion dollars in the US. Both economies are shrinking as a result of the current crisis and Japan has been shrinking for fifteen years. There are no new leadership contenders.

Perhaps having a leaderless world over the last decade could be one of the reasons why many global institutions have had such poor record as this directly reflects the quality of governments. We would not want that aircraft carrier managed by a committee or worse still the politicians we witness every day on our television and yet the leadership of the most important organizations on the planet are not given the same serious attention that any major corporation receives.

I have had considerable dealings over many years with the United Nations and their agencies and related international organizations. Despite arguments about their idealism versus reality, that the work that these organizations undertake always raise, it was a recent article by my friend and colleague

Richard talks about expectations and results at a US government organization that he had been dealing with. His remarks seem more relevant than the lofty political and philosophical explanations usually given about the reasons for the ineffectiveness of the UN, IMF and other global institutions.

It would seem that without effective leadership government organizations in most countries have the same problems as the global institutions – that being

In the majority of global institutions that I have had the opportunity to observe there is definitely a cultural problem in the business sense, but one can also say there is a very obvious lack of leadership. So many times I have seen a total inability to move to the next step on a project most often due to the leadership needed and the requirement to move from talking policy and strategy to being able to actually do something.

When I read comments made in early 2007 by the eminent economist Lord Meghnad Desai about the UN and his praise of the Commonwealth Organization with whom I was having some dealings at the time, I had increased expectation that

There has been a team at UN headquarters since the leadership of Secretary General Koffi Anan just doing this reform ‘The One UN ’ and there are trials of the policy underway, but the evidence of any change in the culture or behavior is difficult to detect. I didn’t see any difference in the way they work at the Commonwealth to that of the UN, perhaps I missed something?

Lord Desai points out: “The Commonwealth sets itself limited goals, no one dominates it and it keeps a low profile. He points out it has often worked better than the United Nations, especially on human rights issues.”

I had the pleasure to meet Lord Desai at the House of Lords in London in March 2007 when I encouraged him and he accepted to join an advisory board for a UN project in Africa. The UN failed to get its act together for this project. They didn’t even bother to follow up on the vast amount of work that had been undertaken – this in some ways confirms his criticism.

My earliest connection with the UN system was while in the conference business, working as coordinating director of the International Congress on Human Relations. Walter Hickel the deputy director of the first UN Conference on the Environment invited me in 1972 to Stockholm. Hickel had been a governor of the State of Alaska and famous for his

In Stockholm, a month or so later, I was overwhelmed by the number of scientists, statesmen and women, and the vast array of people that were there to talk about the global environmental crisis. Margaret Mead, Lady Jackson (Barbara Ward), the famous economist, Rene Dubos the biologist were among the cast of international identities. This was a new experience for me and my first time to attend such a massive talkfest.

I didn’t have the knowledge or understanding at the time that this event was simply a talkfest and although a very big one not much really happened, nevertheless every one important turns up. I met many famous people and it was a great help being in the conference promotion business to gain such easy and plentiful access. Never the less the environmental issues seemed to me to be very much tied to those of leadership and global governance. I wondered at the time what thirty years on these issues would look like. Now I know. The UN remains a talking shop, but the Club of Rome had an important message in 1972 about sustainability and development that was way ahead of its time.

It does

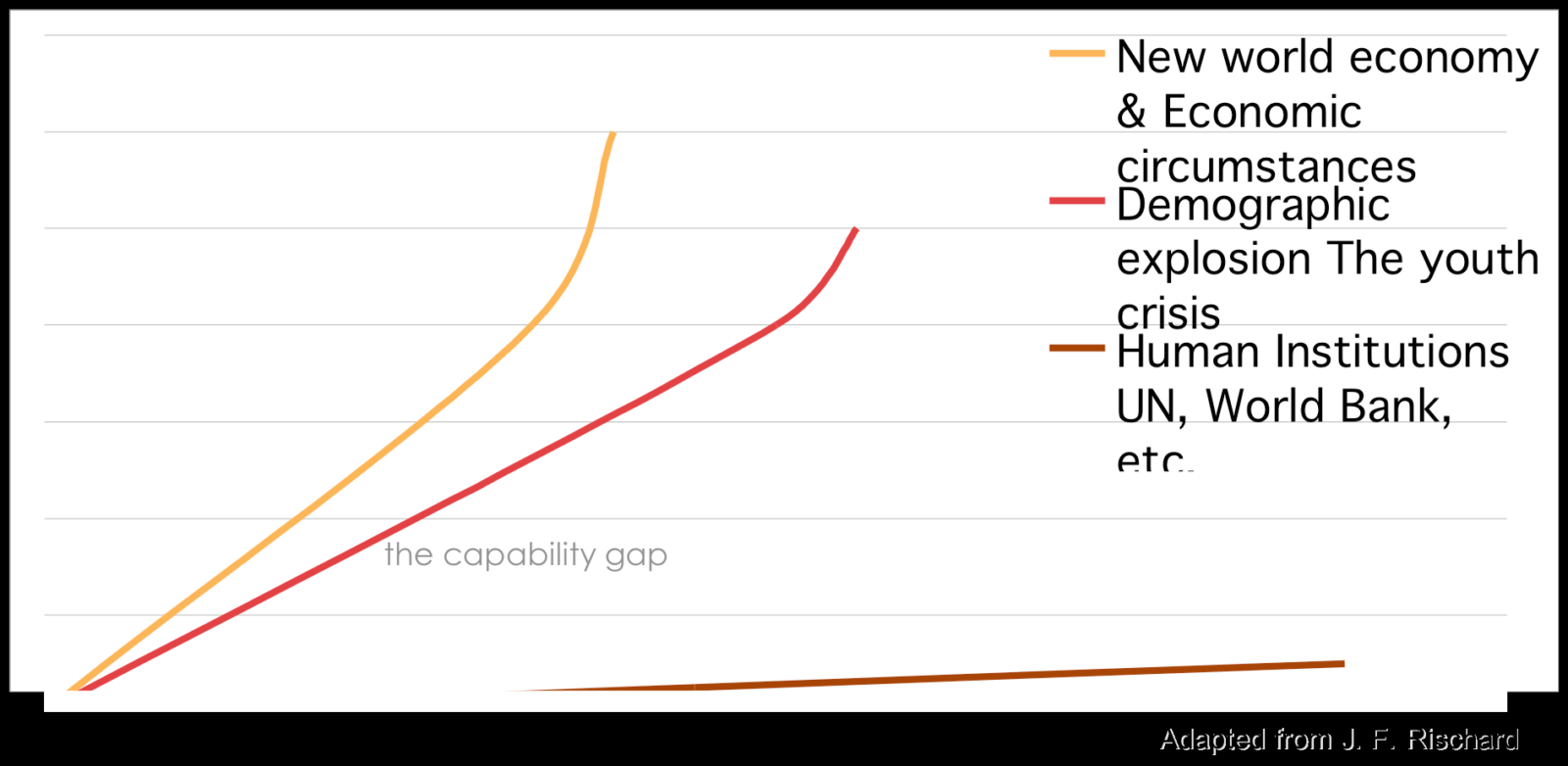

My premise is the capacity of the global institutions simply cannot cope with the increasing gap between the complex problems and their ability to address them. My concern is what these institutions can do about the big global issues and whether there is an alternative?

The financial meltdown is placing great strains on the global institutions and we can be sure a vast amount of financial support will be required to assist developing economies deal with the disruption from the systematic failure of governments and their global governance institutions to deal with the big issues. The IMF, World Bank

There are literally hundreds of meetings conducted by the global institutions every day around the world. 90 to 99 percent of these are about policy, rarely are they about strategy and almost never about execution. Why is this? I believe because execution also requires leadership and this is the domain of people not committees or expert panels or task forces? Policy talk at the UN and the IMF and other organizations is usually a million miles removed from the actually of taking any real action to solve a problem. This is indeed very sad considering the good work that the UN does on some humanitarian fronts.

A meeting of the donors and global institutions has just taken place in Doha, but with the US economy under siege – Europe in recession, many banks in a state of collapse; unemployment on the rise in the majority of countries; and with consumer spending on the decline its very clear the UN’s Millennium Development Goals are threatened. One has to wonder if there still is hope for the 1.4 billion people who live on less than 1.24 dollars per day.

The financial crisis does not stop at the borders of developed countries and it will be the developing countries that are hit hardest with the very poor suffering the most. These people do not have social security nets or savings and they will simply lose the fundamentals of their existence. The IMF warns the crisis has already shifted to the poorer countries and although there is debate on the degree of impact, I believe with a global crisis the worlds poor will not be passed by.

We need global solutions where all countries regardless of their level of development are included. Recent remarks by President Nicolas Sarkozy of France and Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany clearly suggest that the developing countries must not be forgotten in the process of dealing with the financial crisis. The Finance for Development Conference in Doha offered the donors a great potential to agree upon a ‘new global deal for development. If the world can mobilize billions of US dollars to save banks, it should be able to also mobilize the resources to save the world from poverty, hunger and climate change. It is a matter of political will and we will need to pay close attention to the outcomes from the G20 and how the global institutions perform in the year ahead.

My experiences in Asia during the 1980s and 1990s convinced me that there are many practical trade initiatives that can be undertaken to grow business activity that will have a direct affect on poverty reduction. This was long before anyone at the global institutions such as the WTO and others even started to talk about trade – not – aid. Unfortunately trade –not –aid sounds good but again it is a policy statement rather than a set of decisive actions.

Having recently spent a lot of time in Africa I found little difference to those experiences working in Asian countries and again – the issues were usually about leadership. Some times it is the field office that determines what projects are undertaken and this is good if the field office has the required leadership and knowledge. Unfortunately this is often not the case and they defer to HQ as HQ does to them avoiding or delaying a decision. It is an insult to common sense when different institutions produce endless analysis of the same problems all preparing the same or similar reports and never seeming to be able to provide and execute any solutions.

Leadership has been described as learning how to shape the future. Last time, I talked about the leadership challenge that Senator Obama now President Obama would have when taking office. The situation and timing for creating some new reality checks has never been more urgent as governments and business and our best thinkers try to patch up institutional bodies that have had bad track records over long periods. If the same managers are returned to their jobs without new leadership and objectives it is unlikely that institutions such as the IMF will perform any better in the future than in the past.

The crisis has affected more than the global institutions with business organizations also being put on notice. A delegate described the World Economic Forum at Davos a few weeks back as a funereal affair. He went on to say attendees were stunned and beleaguered as they struggled to reconcile a lifelong commitment to small government and non-interventionist policies with the realities rendered from the crisis.

Kevin Rudd the Australian Prime Minister has made the following interesting comments about the financial crisis: “From time to time in human history there occur events of a truly seismic significance, events that mark a turning point between one epoch and the next, when one orthodoxy is overthrown and another takes its place. The significance of these events is rarely apparent as they unfold: it becomes clear only in retrospect, when observed from the commanding heights of history”.

I don’t think Business and Capitalism should be written off as yet and the private sector may even prove to be a resource for finding a new breed of leaders for the global institutions, but clearly there are significant changes necessary if the governments and global institutions are to chart a new course and the leadership skills of the private sector should not be overlooked.

I am not a political scientist but I believe we need shocks similar to that provided by the publication of “Limits to Growth” to deliver a reality jolt. New and effective leadership at the global institutions will be more important than in the past so lets hope that the G20 meeting in April does surprise us all with actions. These organizations have the charter for global governance so if given new responsibilities they had better not just talk more policy. It will take tough and wise leadership and the ability to execute strategy if anything different is to happen.

The OECD another of the global institutions has said we need to make the economy fairer, and we need to share the benefits of prosperity by: Boosting employment and social inclusion Fostering development Providing adequate education and healthcare And only once these conditions and their precursors are met will we be able to look forward to stable growth and increasing prosperity. The long term begins now. We have no time to waste.

Stay tuned in April.

Reymond Voutier 2009